This story will not be a classic account of architecture describing buildings, their uses and their formal appearances. It will be the story, or the visual chronicle, of a brief period of the last century ranging from roughly 1966 to 1973, with illustrations of architectural designs of which some were never meant to be built.

An effort was made during that period to lead architectural design outside of its disciplinary ‘box’ as a functional and compositional organization of construction materials, and to make it, once again, a mental construction of systems of knowledge and of investigation, shifting the focus of the discipline from an activity of problem solving to one of problem finding. My personal research had already started on the tables of the Faculty of Architecture when the political engagement was proceeding in parallel with the attempt in the renovation of the teaching system. The narrative begins in Florence, a city that has been considered the symbol of the Renaissance, of harmony and measure, embodied in the bare-bones minimalism of Brunelleschi, but that intrigued me as student of architecture because of how much it revealed, on the contrary, of a contradictory aspect, on the border between classicism and anticlassicism, of its urban fabric. This contradiction became clear while watching the encounter/collision between a natural phenomenon and an artificial one-when the River Arno burst into the city of Florence in November 1966, transforming the hard, stone support surface of its buildings into a moving liquid mixed with mud and mineral oil.

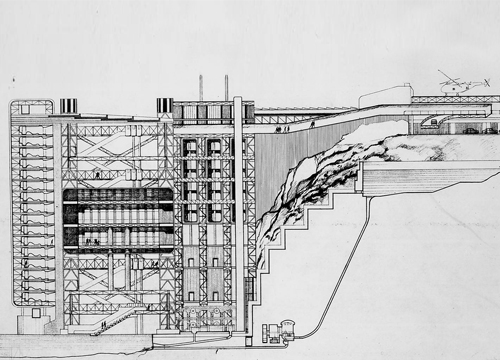

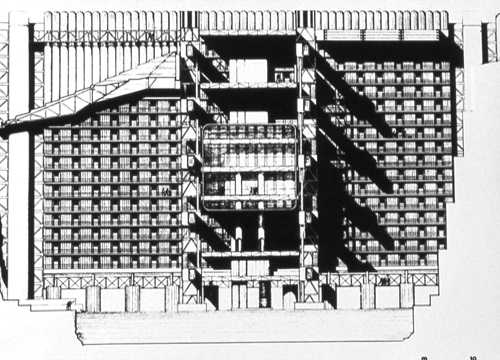

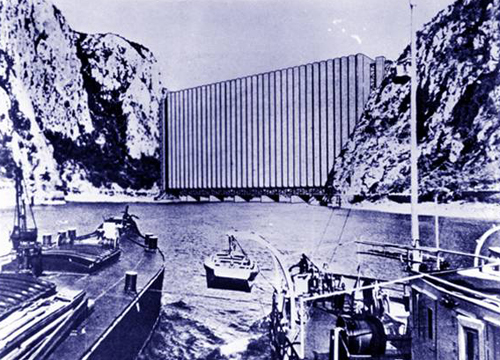

The observation of that dramatic physical substitution, on one hand, posed a radical challenge to the traditional relationship between architecture and ground, and on the other, provoked thought on the relationship between architecture and nature, city and country, interior and exterior-which I brought forth shortly afterwards in my final Thesis project that was half new building design and half restoration of damaged nature. The Vacation Machine, which is part of a body of research entitled Technomorphic Architecture, was an architecture with no street front, with its feet in the sea, that situated most of its space inside a hollow formed by the erosive effect of a torrent on the sandstone ridge to which the building clung, artificially continuing its face. The visual ambiguity of this reconstruction endeavoured to shift architecture’s task toward rebuilding part of the thickness of the Earth’s outer envelope, considered as the body of that ‘spaceship’ described by Buckminster Fuller as a single large ecological system. In this way my thesis attempted to exorcize that image that had been with us all the way from Futurism to Archigram, in which the architecture of the industrial era had to be structured like a machine, or better yet a motor, just as the city was assimilated to the mechanical rationality of the factory. This new ambiguous relationship between nature and architecture alluded to the passage from Hans Hollein’s ”Alles ist Architektur” to the concept that ”everything is landscape”: architecture and landscape are no longer distinct entities; architecture can restore the landscape by occupying the non-places -voids resulting from natural actions- recovering interrupted layers for architecture itself. Architecture is reduced to a neutral, transparent surface as a further layer on the surface of Spaceship Earth, just as homes can be dug into the earth or utilize folds, while the whole functions as a diachronic theatre without walls, but with mobile systems. The office becomes landscape, and the landscape enters the museum.