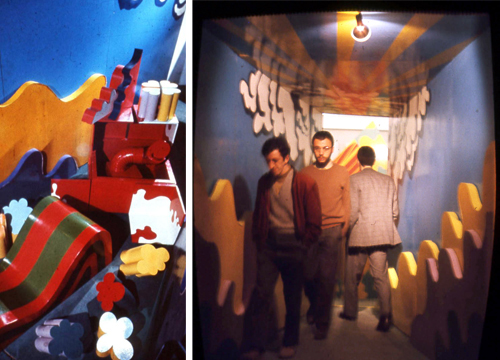

December 1966 witnessed the birth, from the mud of the Florence flood, of Superstudio, which I founded with Adolfo Natalini: The same year saw the first exhibition of Superarchitecture, for which the poster read: ”Superarchitecture is the architecture of superproduction, of superconsumption, of superpersuasion to consume, of the supermarket, the superman, of superoctane gasoline. Superarchitecture accepts the logic of production and consumption, and works for its demystification.”

Here began a course of action based upon the conviction that architecture was a means of changing the world: designs were hypotheses of physical transformations; they were ways of hypothesizing different quantities and qualities.

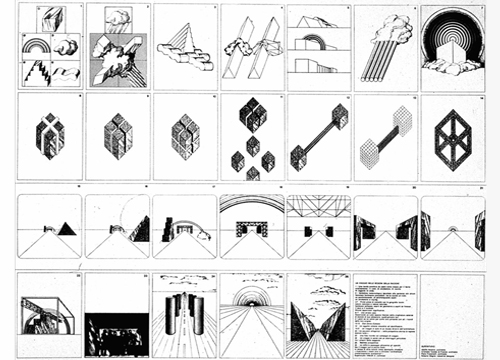

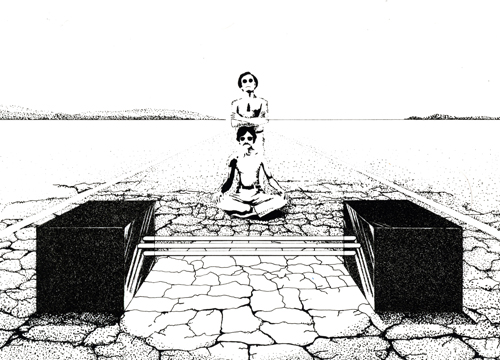

These early works were collected in a panel entitled A Journey in the Regions of Reason

.

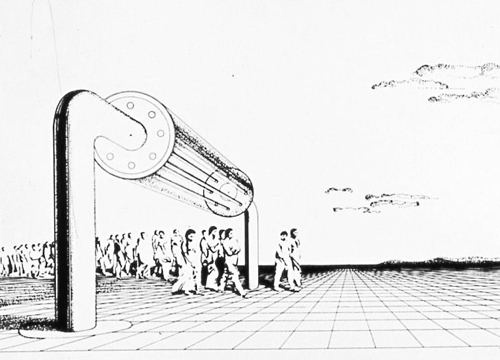

Twentieth-century architecture established a preferential relationship with industry, which it took as a model, adopting its rational logic and building technologies. This strategic alliance permitted architecture to renew itself formally, and industry to propose itself as a model for world change.

Superstudio criticized the attempt to unify the cultures of the system of technologies, from design to the city, in the name of rational necessity. That logic produced an object perfectly reproducible by industry and therefore final: the design transformed the needs of production into rational values.All-production man sublimates his bourgeois ambitions in a existenz minimum surrounded by utensil objects whose form is determined by the function they serve.

In a word: twentieth-century mechanical man must use final objects within minimal architecture in a city organized rationally as a factory through the system of zoning.

But the working class rejected the factory as a social model and pursued middle-class models instead, while capital, in order to grow and multiply, rejected the final design and demanded a continuous renewal of models that would keep the continuous desire to consume alive.

In the sixties, Superstudio the key for reading this reality on its head: the complexity, contradictions and discontinuity that exist in the physical and social world are by no means destined to vanish from the order of an industrialized world because they are the ripest fruits of industry’s growth in the world.

Chaos is a permanent, not a provisional, reality.

The avant-gardes must assume the burden of ”making good” (as creative possibility) that which, until yesterday, was considered ill or dissonant.